On this day, 25 September 1703 died Archibald Campbell, the 10th Earl and 1st Duke of Argyll……..which Argyll was this one then…?

This Archibald, hereinafter to be referred to as Our Archibald, was the latest in a long line of ennobled Archibald Campbells who held title over Argyll in the centuries after Colin Campbell was first raised to the peerage as the 1st Earl of Argyll by James II, in 1457.

A contemporary of Claverhouse, born in 1658, he played as much a part on the grand stage of Scottish Affairs as any of his forefathers. Which is why he features in this blogpost.

It can be difficult for even the enthusiastic student of Scottish History to keep track of the various Earls, Dukes and Marquesses who ruled the House of Argyll through the centuries. Suffice to know that most of these were christened Archibald and the vast majority were heinous criminals. Men fueled by towering ambition both for themselves and their noble house and, since the advent of the Reformation in the 16th century, the bitter, cheerless gall of hard core Presbyterianism layered a further patina of unpleasantness on them and their actions.

As the 10th Earl, Our Archibald was the son of Archibald, the 9th Earl who was executed in 1685 for his involvement in the Monmouth Rebellion.

This was naked attempt to overthrow the incumbent of the British throne, James II & VII and place the Duke of Monmouth, Charles II’s illegitimate offspring, there in his stead.

Much has been written of Monmouth’s part of the rebellion but there is comparatively little commentary on Argyll’s efforts with the Scottish aspect of the rebellion.

Monmouth, having landed at Lyme Regis in June 1685 with less than 100 men, was quickly reinforced by local volunteers to the tune of 1000 troops. Over the next 4 weeks his army fought a serious of indecisive skirmishes against royalist troops before he was brought to a definitive set-piece battle at Sedgemoor a month after landing where his poorly trained and disorganized force was utterly routed by the regulars of the King’army. Monmouth was duly executed for high treason.

If Monmouth’s end of the rebellion was comical, Argyll’s efforts north of the border degenerated swiftly to the farcical. Arriving in Orkney a month before Monmouth docked at Lyme Regis, Archibald spent 4 weeks sailing around the west coast attempting to round up supporters for his cause. Bedevilled by lack of support and mutiny amongst those who did rally to his colours, he finally found himself at Dumbarton with only his son and 3 friends by his side. Subsequently captured by Government troops Argyll was executed in Edinburgh fully one week prior to Monmouth’s denouement at Sedgemoor.

This Archibald, the 9th Earl, features in the Claverhouse story as much as Our Archibald, the 10th Earl. To his credit he fought for his king and Scotland against the depredations of Cromwell and took part in both military disasters of the Battle of Dunbar in 1650 and then the Battle of Worcester the following year. He survived through the interregnum, keeping one foot on both Stuart and Cromwellian camps, trusted by neither and viewed with high suspicion by both. And his father, Archibald the 8th Earl was executed on Charles II command in the immediate aftermath of the restoration in 1660.

In the complicated political atmosphere post the Restoration, Archibald the 9th Earl, sought to navigate the difficult waters but was confounded by the passing of the Test Act in 1681. This required all the nobility to take an oath which required a profession of the Protestant religion AND an affirmation of royal supremacy in all matters spiritual and temporal. This created too much of a compromise for Archibald who refused to take the oath and was, consequently, tried before his peers in December 1681, with one John Graham of Claverhouse present on the jury, he was sentenced to death. But prior to his execution he managed to escape from Edinburgh Castle, in disguise, and abetted by his step daughter Lady Sophie Lindsay. He was eventually executed, as outlined above, following the failure of Monmouth’s Rebellion.

[pic]

Our Archibald’s grandfather was the 8th Earl, also christened Archibald, and it was he who felt the eventual wrath of Charles II, when the Stuart monarchy was restored in 1660 following that disastrous period of miserableness known to history as the Cromwellian interregnum. It was he who set himself against the Great Montrose and although bested by this outstanding hero of Scottish history both on the military and political stage, he was the man peering through the blinds of his Edinburgh home on 20th May 1650 when Montrose was put to death at the order of the misguided covenanting Government.

Our Archibald’s grandfather, also Archibald. 8th Earl and 1st Marquess of Argyll. In black-cowled Geneva Minister manifestation

Anyway, let’s get back to Our Archibald, the 10th Earl. He had much to live up to, given the extensive record of his father and grandfather, both of whom had been executed for high treason, and he applied himself enthusiastically to his task. Following King James’ accession to the throne in 1685, after the death of Charles II, Archibald enthusiastically lobbied for the restoration of his father’s attainder. And when his entreaties were treated with the contempt of which they were thoroughly deserving, Archibald took himself off to The Hague and the Court of the Prince of Orange where he joined the motley crew of ambitious, exiled men who were minded to persuade the young Prince to seek his father-in-law’s throne for himself.

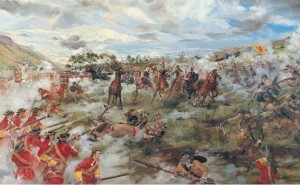

With the usurpation of King James from the throne in December 1688, Archibald continued in his personal support of the new monarchs, William and Mary. A devotion which in turn led to the restoration of his father’s land and holdings. When Dundee raised King James’ Standard on Dundee Law in April 1689, and initiated the first Jacobite Rising which was intended to restore James to said throne, Our Archibald proceeded to raise an armed force in King William’s name to protect the Hanoverian Crown. Although, this was done in such a slow and haphazard fashion that the decisive action of that campaign had been fought at Killiecrankie ere an armed Campbell marched forth from Argyll.

The Battle of Killiecrankie, July 1689. Fought without contribution from Archibald or his Campbell’s

With the eventual end of Dundee’s campaign it was clear to many that with a monarch of satisfactory protestant heritage ensconced on the throne, and an ambitious and capable one at that, the deposed Stuart monarch and his court exiled in France and the shifting political sands of the last ninety years now beginning to solidify into set cement, the requirement for caution of loyalty, often manifested as outright duplicity, was now gone. And it was now possible for a noble lord to throw himself wholeheartedly behind the monarch in order to best profit one’s standing and the resultant inheritance to be handed down. It was in this climate of enthusiastic loyalty that Our Archibald found himself. He became William’s principal advisor on Scottish affairs and was made a Privy Councillor. On the military side he was made Colonel-in-Chief of the Earl of Argyll’s Regiment of Foot. This was the body of men who were entrusted by William’s Scottish advisors to carry out that action of political repression known to us all as the Massacre of Glencoe, in 1692. Although, to be fair to Our Archibald, he was far and distant from the aforementioned Glen when the slaughter of the women and children was taking place.

The Massacre of Glencoe, February 1692. Carried out by The Earl of Argyll’s Regiment of Foot of which Our Archibald was Colonel-in-Chief.

Elevated to 1st Duke of Argyll in 1701 by a grateful monarch he died on 25th September 1703 at Cherton House, near Newcastle-upon-Tyne. His son, John, not Archibald, continued to serve the Hanoverian house in the same loyal fashion and indeed commanded the detachment of the British Army which, at the Battle of Sheriffmuir, confounded the Earl of Mar’s attempts to move south during the 1715 Jacobite Rising. An afternoon’s action which effectively ended the Rising.

Our Archibald’s son, John. The first head of the House of Argyll in 4 generations not christened Archibald.

Tagged: 9th Earl of Argyll, battle of sheriffmuir, James II, Killiecrankie, MArquess of Argyll, Massacre of Glencoe, Montrose

John Graham of Claverhouse. Bonnie Dundee.

John Graham of Claverhouse. Bonnie Dundee.

[…] A cold and clinical assessment of that day, however, would decide that King George’s man, the Duke of Argyll, in preventing Mar’s army from heading south into England and joining forces with the Jacobite […]

LikeLike