On this day in 1638 the National Covenant was signed in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh.

The Signing of the National Covenant

It was not the first such covenant to be drawn up and publicly signed in Presbyterian Scotland. Nor, sadly would it be the last. However, it was the most significant and its effects more far reaching and profound than any of those previously penned.

In the fifty one years that were to pass from this momentous day until William’s usurpation of James VII & II in 1689, this document would lead directly to the violent death of more Scots than the Great War of 1914 – 18.

A concept originally inspired by the Old Testament covenants between the Israelites and their god, the covenant idea had been reinforced in the reformist teachings of Luther and Calvin in the 15th century.This National Covenant drew from the first covenant penned by the Lords of Congregation in 1557, in response to their outrage at the proposed marriage of the young Mary, Queen of Scots to the future King of France. It also leaned heavily on the Negative Confession of Faith signed by James VI in 1581.

Penned by two men, Archibald Johnston, a lawyer, and Alexander Henderson, a Presbyterian minister, it was both a brilliant concept and an inspired piece of writing and it was entirely unprecedented in European history.

Archibald Johnston, co-author of the National Covenant

The sequence of events that led to its creation began in 1603 when James VI of Scotland became also King of England and Ireland on the death of Elizabeth. Scotland and the Scots were now in a new and confusing relationship, neither bound politically with England nor an entirely separate state. James, much to his credit, held it all together for 22 years until his death in 1625. However, under his son, Charles I, the wheels began to come off the bus of royal rule. By 1637 England and Ireland were in complete turmoil and the Scots, in simple terms, launched a revolution.

Charles I

Charles was hell bent on having a unified form of religious observance throughout his three kingdoms and this would not be Calvinist in nature. In Scotland in 1636 he issued a new set of rules for worship: the Canons and Constitutions Eclesiasticall, which drew heavily on the Church of England’s rule-book of 1604. Historically any fundamental changes to the nature of worship in Scotland had been thrashed out and handed down by the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland. Charles, however, enthusiastically sought to bend the Presbyterian towards the Anglican, and imposed these changes by simple royal prerogative.

In the same arbitrary manner a new Common Prayer Book was issued on 23 July 1637. The king was playing fast and loose with one thing that meant a great deal to the common people of Scotland – how they worshipped their god. Public outrage grew.

On the day many ministers simply ignored the command to use the new prayer book. When the Bishop of Brechin placed it on his lectern before his glowering congregation it was flanked ostentatiously with two loaded pistols. In St Giles Cathedral, when the minister began to read from it Jenny Geddes famously picked up her stool and threw it at him.

Jenny Geddes hurls her stool at the minister in St Giles

Jenny Geddes hurls her stool at the minister in St Giles

And so the crisis developed. Support for the King’s changes was thin on the ground at all levels of society and opposition was loud, vehement and growing apace. In January 1638 the Scottish Privy Council, the executive agency of Royal Government, was compelled to meet in Stirling, such was the level of civil disturbance in Edinburgh.

The protesters then took a major step when they set up a parallel authority to the Council, known as the ‘Tables’. This had representation from each of the four estates of the kingdom; nobles, gentry, burgesses and clergy. It did not, however, have any constitutional authority whatsoever. But it became the focus of the protests of the nation.

It was this demand for meaningful protest and effective action that led directly to the National Covenant being drafted by Johnston and Henderson. On 27th February this first draft was read to a gathering of nobles and ministers and some tinkering carried out. The following afternoon after a religious ceremony in Greyfriars it was solemnly displayed and duly signed by the nobility, the lesser barons and the gentry.

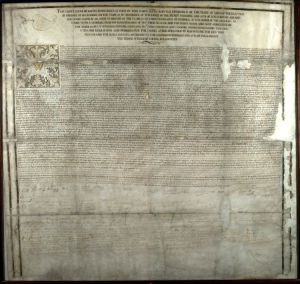

The National Covenant itself

Prominent on this document even now, over 370 years later, is the bold and clear signature of Montrose. James Graham, 5th Earl, soon to be 1st Marquis. One of the first to pen his signature in protest at the King’s high-handedness, he would be Charles I’s Captain-General in the war that ripped across Scotland six years later. But we’ll deal with that in another post.

[  The Marquis of Montrose, among the first signatories

The Marquis of Montrose, among the first signatories

By 2nd March there were multiple copies circulating throughout the kingdom as the common people queued up for hours to make their mark on the rebellious parchment.

The brilliance of the document itself and its utilisation as a tool to bring about change can be seen in a number of ways. Firstly it coalesced a national feeling of agitation which was initially undirected. It also effectively formed a platform to license further action. Carefully phrased it would cause upset to no-one of a protestant persuasion regardless of their position on its extensive spectrum. For although Henderson and Johnston were vehemently opposed to the very idea of Bishops, since the purest Presbyterian faith required only the minister between each honest soul and his god, no mention of bishops was made in the text. Thus it would not alienate any of an Episcopalian persuasion, who in turn, were signing in protest at what they saw as the king’s attack on the authority of their Bishops.

Additionally, the National Covenant involved all signatories on an equal basis, regardless of their rank in society, and it demanded unequivocal commitment from each of them. Furthermore, by referring to the Negative Confession of 1581 and various other subsequent Acts of Parliament it highlights that all Scots were in law and duty bound to maintain “God’s true religion” ie Presbyterianism and that said religion was joined with the King’s authority. Thus ingeniously linking loyalty to the king with, but subordinate to, loyalty to the Kirk. There was further emphasis to clarify that loyalty to the king was dependent on “blessed and loyal conjunction” with the true religion.

Implicit in this wording was the notion that any king who tampers with the ‘true religion’ must be resisted. This justification for armed resistance against the monarch made the National Covenant a rebellious document. However, the clear implication that an individual could set his private conscience against his obligations to the King and the State made it revolutionary. And so all signatories who had hitherto merely been supplicants to the King now had a new name…..Covenanters.

John Graham of Claverhouse. Bonnie Dundee.

John Graham of Claverhouse. Bonnie Dundee.

Recent Comments